C++17 is a version of the C++ programming language that was standardized in 2017, and adds additonal new features and improvements to what is considered “modern C++”. Some major new features that I have really loved in C++17 include:

- Structured bindings: Allows you to easily extract multiple variables from a single tuple or struct, and to use them in a more readable way.

- Inline variables: Allows for the definition of variables with the “inline” keyword in classes and elsewhere.

- New attributes: Allows for more readable code by marking certain areas with specific attributes that the compiler understands.

- std::shared_mutex: Allows for multiple “shared” locks and a single “exclusive” lock. This is basically a standard read/write mutex!

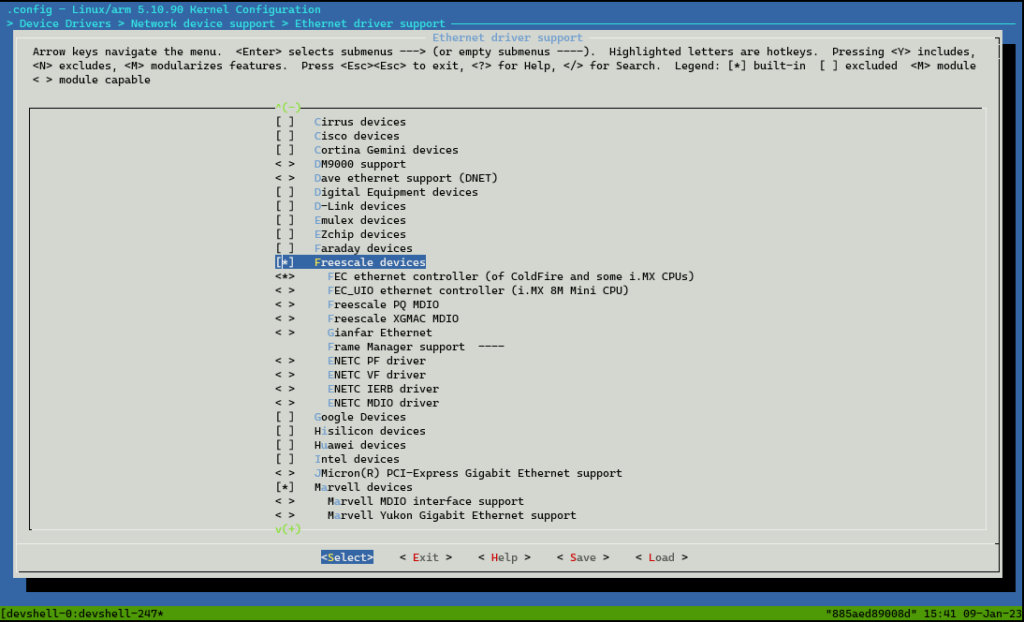

In embedded systems, support for C++17 will depend on the compiler and platform you are using. Some more popular compilers, such as GCC and Clang, have already added support for C++17. However, support for C++17 for your project may be limited due to the lack of resources and the need to maintain backwards compatibility with older systems.

A good summary of the new features and improvements to the language can be found on cppreference.com. They also provide a nice table showing compiler support for various compilers.

Structured Bindings

I already wrote about my love for structured bindings in another post (and another as well), but this article would be incomplete without listing this feature!

My main use of structured bindings is to extract named variables from a std::tuple, whether that be a tuple of my own creation or one returned to me by a function.

But I just realized there is another use for them that makes things so much better when iterating over std::maps:

// What I used to write

for (const auto &val : myMap)

{

// Print out map data, key:value

std::cout << val.first << ':' << val.second << std::endl;

}

// What I now write

for (const auto &[key, value] : myMap)

{

// Print out map data, key:value

std::cout << key << ':' << value << std::endl;

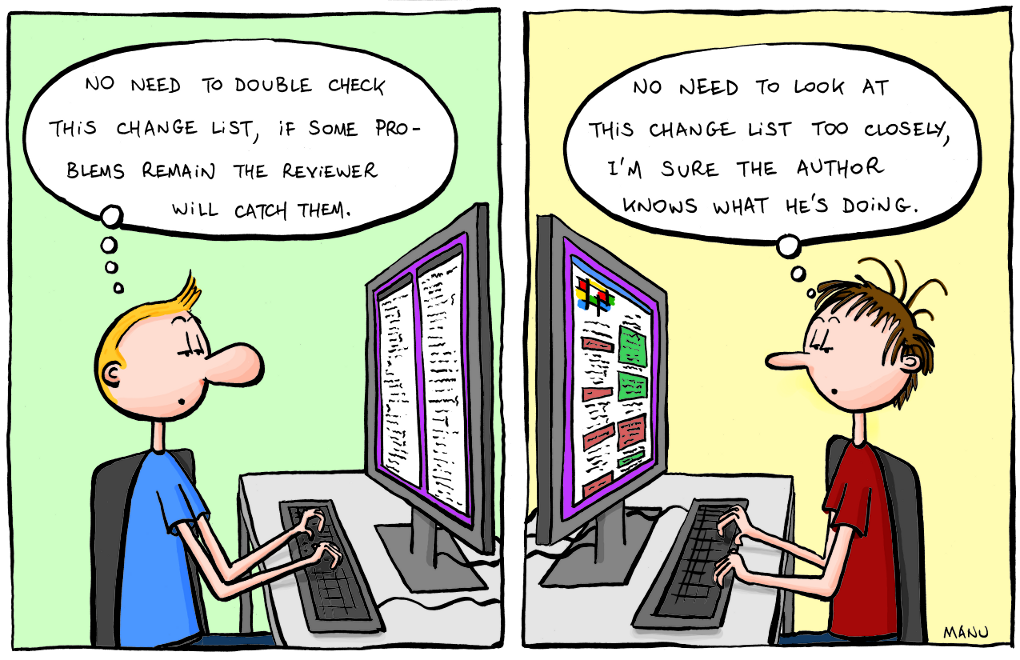

}Code language: PHP (php)The second for loop is much more readable and much easier for a maintainer to understand what is going on. Conscious coding at its best!

Inline Variables

An inline variable is a variable that is defined in the header file and is guaranteed to be the same across all translation units that include the header file. This means that each compilation unit will have its own copy of the variable, as opposed to a single shared copy like a normal global variable.

One of the main benefits of inline variables is that they allow for better control over the storage duration and linkage of variables, which can be useful for creating more flexible and maintainable code.

I find this new feature most useful when declaring static variables inside my class. Now I can simply declare a static class variable like this:

class MyClass

{

public:

static const inline std::string MyName = "MyPiClass";

static constexpr inline double MYPI = 3.14159265359;

static constexpr double TWOPI = 2*MYPI; // note that inline is not required here because constexpr implies inline

};Code language: PHP (php)This becomes especially useful when you would like to keep a library to a single header, and you can avoid hacks that complicate the code and make it less readable.

New C++ Attributes

C++17 introduces a few standard attributes that make annotating your code for the compiler much nicer. These attributes are as follows.

[[fallthrough]]

This attribute is used to allow case body to fallthrough to the next without compiler warnings.

In the example given by C++ Core Guidelines ES.78, having a case body fallthrough to the next case leads to hard to find bugs, and it just is plain hard to read. However, there are certain instances where this is absolutely appropriate. In those cases, you simply add the [[fallthough]]; attribute where the break statement would normally go.

switch (eventType) {

case Information:

update_status_bar();

break;

case Warning:

write_event_log();

[[fallthough]];

case Error:

display_error_window();

break;

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)[[maybe_unused]]

This attribute is used to mark entities that might be unused, to prevent compiler warnings.

Normally, when writing functions that take arguments that the body does not use, the approach has been to cast those arguments to void to eliminate the warning. Many static analyzers actually suggest this as the suggestion. The Core Guidelines suggest to simply not provide a name for those arguments, which is the preferred approach.

However, in the cases where the argument is conditionally used, you can mark the argument with the [[maybe_unused]] attribute. This communicates to the maintainer that the argument is not used in all cases, but is still required.

RPC::Status RPCServer::HandleStatusRequest(

const RPC::StatusRequest &r [[maybe_unused]])

{

if (!m_ready)

{

return RPC::Status();

}

return ProcessStatus(r);

}Code language: PHP (php)This attribute can also be used to mark a static function as possible unused, such as if it is conditionally used based on whether DEBUG builds are enabled.

[[maybe_unused]] static std::string toString(const ProcessState state);Code language: PHP (php)[[nodiscard]]

This attribute is extremely useful when writing robust and reliable library code. When marking a function or method with this attribute, the compiler will generate errors if a return value is not used.

Many times, developers will discard return values by casting the function to void, like this.

(void)printf("Testing...");Code language: JavaScript (javascript)This is against the Core Guidelines ES-48, but how do you get the compiler to generate errors for your functions in a portable, standard way? With [[nodiscard]]. When a developer fails to check the return value of your function (i.e., they don’t store the result in some variable or use it in a conditional), the compiler will tell them there is a problem.

// This code will generate a compiler error

[[nodiscard]] bool checkError(void)

{

return true;

}

int main(void)

{

checkError();

return 0;

}

// Error generated

scratch.cpp:36:13: error: ignoring return value of ‘bool checkError()’, declared with attribute ‘nodiscard’ [-Werror=unused-result]

36 | checkError();

// However, this takes care of the issue because we utilize the return value

if (checkError())

{

std::cout << "An error occurred!" << std::endl;

}Code language: JavaScript (javascript)I love how this can be used to make your users think about what they are doing!

Shared (Read/Write) Mutex

A shared lock allows multiple threads to simultaneously read a shared resource, while an exclusive lock allows a single thread to modify the resource.

In many instances, it is desirable to have a lock that protects readers from reading stale data. That is the whole purpose of a mutex. However, with a standard mutex, if one reader holds the lock, then additional readers have to wait for the lock to be released. When you have many readers trying to acquire the same lock, this can result in unnecessarily long wait times.

With a shared lock (or a read/write mutex), the concept of a read lock and a write lock are introduced. A reader must wait for the write lock to be released, but will simply increment the read lock counter when taking the lock. A writer, on the other hand, must wait for all read and write locks to be released before it can acquire a write lock. Essentially, readers acquire and hold a shared lock, while writers acquire and hold an exclusive lock.

Here is an example of how to use a shared_mutex:

#include <iostream>

#include <thread>

#include <mutex>

std::shared_mutex mtx;

int sharedCount = 0;

void writevalue()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; ++i)

{

// Get an exclusive (write) lock on the shared_mutex

std::unique_lock<std::shared_mutex> lock(mtx);

++sharedCount ;

}

}

void read()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 10000; ++i)

{

// Get a shared (read) lock on the shared_mutex

std::shared_lock<std::shared_mutex> lock(mtx);

std::cout << sharedCount << std::endl;

}

}

int main()

{

std::thread t1(writevalue);

std::thread t2(read);

std::thread t3(read);

t1.join();

t2.join();

t3.join();

std::cout << sharedCount << std::endl;

return 0;

}

Code language: C++ (cpp)Here you can see that std::shared_mutex is used to protect the shared resource sharedCount. Thread t1 increments the counter using an exclusive lock, while threads t2 and t3 read the counter using shared locks. This allows for concurrent read operations and exclusive write operation. It greatly improves performance where you have a high number of read operations versus write operations.

With C++17, this type of lock is standardized and part of the language. I have found this to be extremely useful and makes my code that much more portable when I need to use this type of mutex!

C++17 offers a wide range of new features that provide significant improvements to the C++ programming language. The addition of structured bindings, inline variables, and the new attributes make code more readable and easier to maintain, and the introduction of the “std::shared_mutex” type provides performance improvements in the situations where that type of lock makes sense. Overall, C++17 provides an even more modern and efficient programming experience for developers. I encourage you to start exploring and utilizing these new features in your own projects!