A lot has been written on design patterns, but they were woefully absent in my education as a developer. I learned about them after a few years as a developer, and they were game-changing for me. In this post, I want to share with you a few of the most useful design patterns for C/C++ that I often use in my own designs.

What are Design Patterns?

When I first learned about design patterns, they were presented to me as the proper way to organize classes to solve specific types of problems. In fact, the first design pattern I was introduced to was the state pattern for implementing state machines. Up until that point, I was resorting to complex case statements with lots of conditional checks to implement my state machine logic, simply because that was all I knew.

I was taught that I could encapsulate all the transition logic into state classes. I was blown away by how much that single refactor could simplify my code, and how much easier it was to add and remove states.

Over time, I started to find that the state pattern applied to so many other problems, and then that got me into trouble. I had this shiny new tool in my toolbox and I just wanted to use it for everything!

When Should Patterns Be Applied?

Thanks to some great mentors, I was able to step back and start looking at other patterns that existed — the factory pattern, adapters, singletons, and strategies. All of these different tools could be used in my designs to solve different problems.

And that is the key — design patterns are tools, nothing more. As with any tool in your toolbox, there is a time and place to use it. Design patterns are no different. For C/C++ developers, they can lead to some strikingly simple and elegant solutions, but sometimes they can be a rabbit hole that will just add unnecessary abstraction to your code when a simple, straightforward solution would do.

As conscious developers, our goal is to design amazing applications, using the best tools available to us. We understand that if a certain tool does not work for a given problem, we move on. We don’t try to force a tool on a design, which is one of the major pitfalls for new developers once they learn about design patterns.

Types of Design Patterns

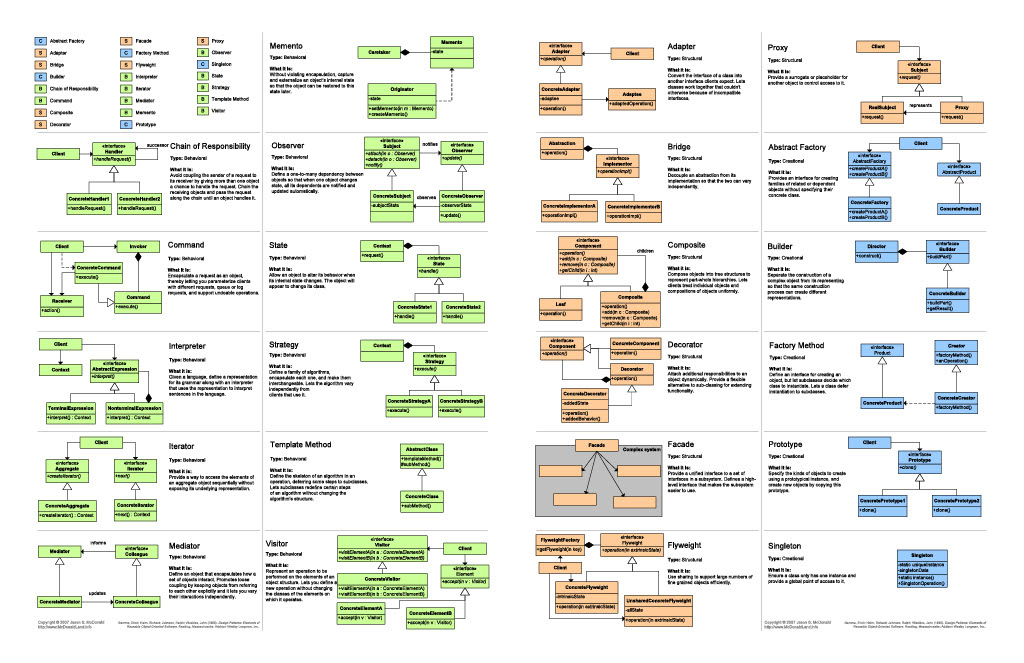

The literature on design patterns typically breaks all the common patterns down into three primary categories, each of which deal with a different aspect of the development process:

- Creational Patterns

- Structural Patterns

- Behavioral Patterns

I’m going to share with you a few of my favorite design patterns from each category. You can find tons of information about design patterns through a simple search, however one resource I have found extremely valuable is refactoring.guru. That site has lots of good information, all of which can be applied to being a conscious developer!

Creational Design Patterns

Creational design patterns are used in software development to provide a way to create objects in a flexible and reusable way. They help to encapsulate the creation process of an object, decoupling it from the rest of the system. This makes it easier to change the way objects are created or to switch between different implementations.

Creational design patterns provide a variety of techniques for object creation, such as abstracting the creation process into a separate class, using a factory method to create objects, or using a prototype to create new instances. These patterns are useful when the creation of objects involves complex logic or when the object creation process needs to be controlled by the system.

Some examples of creational design patterns include the Singleton pattern, which ensures that only one instance of a class is created, and the Factory pattern, which provides a way to create objects without specifying the exact class of object that will be created.

Overall, creational design patterns help to improve the flexibility and reusability of software systems by providing a more structured and standardized approach to object creation.

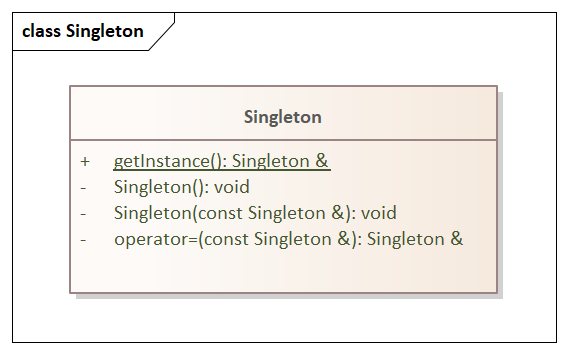

Singleton Creational Pattern

The Singleton design pattern is a creational pattern that ensures that a class has only one instance and provides a global point of access to that instance. This pattern is useful in situations where only one instance of a class should exist in the program, such as managing system resources or ensuring thread safety. However, it should be used with caution, as it can introduce global state and make testing more difficult.

In C++, this can be achieved by doing two things:

- Make the constructor for your class private.

- Provide a static method to access the singleton instance.

The static method creates the singleton instance the first time it is called and returns it on subsequent calls. Ultimately, this static method typically returns either a reference to the newly created class, or a pointer to it. I prefer to use references because they are safer, but there have been cases where I create a std::shared_ptr in my static function and return that to the caller to access the singleton.

C++ Example of the Singleton Creational Pattern

To implement the Singleton pattern in C++, a common approach is to define a static method in the class definition. Then, in the implementation file, define the static method and have it define a static member variable of the class type. The static method will initialize the singleton instance if it has not been created yet, and return it otherwise. Here’s an example:

class Singleton {

public:

static Singleton& getInstance() {

static Singleton instance; // The singleton instance is created on the first call to getInstance()

return instance;

}

private:

Singleton() {} // The constructor is private to prevent typical instantiation

Singleton(const Singleton&) = delete; // Delete the copy constructor to prevent copying

Singleton& operator=(const Singleton&) = delete; // Delete the assignment operator to prevent copying also

};

Code language: C++ (cpp)In this example, the getInstance() method returns a reference to the Singleton instance, creating it on the first call using a static variable. The constructor is private to prevent instantiation from outside the class. The copy constructor and assignment operator are deleted to prevent copying.

Your getInstance() method can take arguments as well and pass them along to the constructor, if that is desired. You need to be aware that those are only used to create the object the first time, and never again. For this reason, I consider it to be best practice for getInstance() to not take any arguments to not confuse a user making a call.

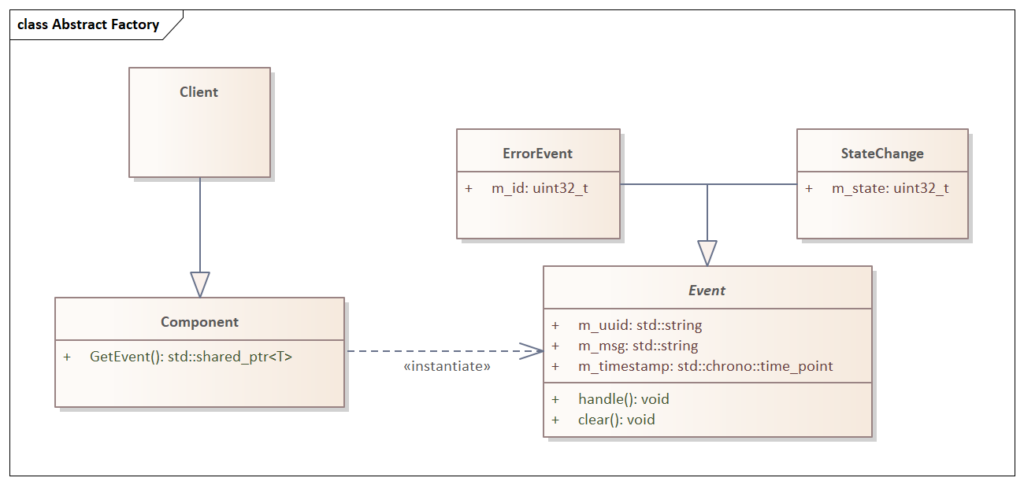

Abstract Factory Creational Pattern

The Abstract Factory design pattern is a creational pattern that provides an interface for creating families of related objects without specifying their concrete classes. This pattern is useful in situations where there are multiple families of related objects, and the actual type of object to be created should be determined at runtime. For example, in a messaging application, there might be multiple types of messages that need to be created. Each type of message should be consistent in interface, but with specific behavior.

C++ Example of the Abstract Factory Creational Pattern

In C++, this can be achieved by defining an abstract base class for each family of related objects. Then define concrete subclasses for each type of object in each family. Here’s an example from a recent project of mine:

struct Event {

std::string m_uuid; // define a UUID for the event

std::string m_msg; // message related to the event

std::chrono::time_point m_timestamp; // time event occurred

virtual ~Event () {}

virtual void handle() = 0;

virtual void clear() = 0;

};

struct ErrorEvent : public Event {

uint32_t m_id; // Error ID for the specific error that occurred

void handle() override {

// Perform "handling" action specific to ErrorEvent

}

void clear() override {

// Perform "clear" action specific to ErrorEvent

}

};

struct StateChange : public Event {

uint32_t m_state; // state identifier

void handle() override {

// Perform "handling" action specific to StateChange

}

void clear() override {

// Perform "clear" action specific to StateChange

}

};

class Component {

public:

template <

class T,

std::enable_if_t<std::is_base_of_v<Event, T>, bool> = true>

std::shared_ptr<T> GetEvent(void)

{

return std::make_shared<T>();

}

};

Code language: C++ (cpp)In this example, the Event base class defines virtual methods for handling the event and clearing the event. The ErrotEvent and StateChange classes are concrete subclasses that implement these methods for the specific events. The Component class defines a GetEvent() methods for creating Events. Now, when I want to create a new event, I just inherit the Event base class and can call GetEvent() to create a new instance of the event.

Pay special attention to lines 37. This ensures that the compiler will give an error if I try to call GetEvent with a data type that is not derived from my Event class. And that is ideal — turning what were once run time errors into compiler errors.

This is just one use of the Abstract Factory pattern. There are others that allow you to define specific behavior for different platforms or architectures as well!

Structural Design Patterns

Structural design patterns are used in software development to solve problems related to object composition and structure. These patterns help to simplify the design of a software system by defining how objects are connected to each other and how they interact.

Structural design patterns provide a variety of techniques for object composition, such as using inheritance, aggregation, or composition to create complex objects. They also provide ways to add new functionality to existing objects without modifying their structure.

Some examples of structural design patterns include the Adapter pattern, which allows incompatible objects to work together by providing a common interface, and the Decorator pattern, which adds new behavior to an object by wrapping it with another object.

Overall, structural design patterns help to improve the modularity, extensibility, and maintainability of software systems by providing a more flexible and adaptable way to compose objects and structures. They are particularly useful in large and complex software systems where managing the relationships between objects can become challenging.

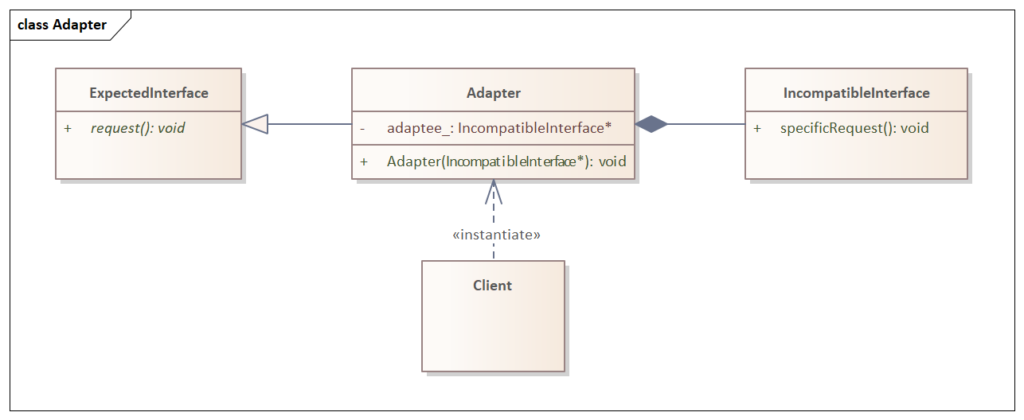

Adapter Structural Pattern

The Adapter design pattern is a structural pattern that allows incompatible interfaces to work together. In C++, this pattern is used when a class’s interface doesn’t match the interface that a client is expecting. An adapter class is then used to adapt between the two interfaces.

C++ Example of the Adapter Structural Pattern

To use this in C++, define a class that implements the interface that the client expects, and internally use an instance of the incompatible class that needs to be adapted. Here’s an example:

class ExpectedInterface {

public:

virtual ~ExpectedInterface() {}

virtual void request() = 0;

};

class IncompatibleInterface {

public:

void specificRequest() {

// Perform some specific request

}

};

class Adapter : public ExpectedInterface {

public:

Adapter(IncompatibleInterface* adaptee) : adaptee_(adaptee) {}

void request() override {

adaptee_->specificRequest();

}

private:

IncompatibleInterface* adaptee_;

};

Code language: C++ (cpp)In this example, the ExpectedInterface class defines the interface that the client expects, which is the request() method. The IncompatibleInterface class has a method called specificRequest() that is not compatible with the ExpectedInterfaceAdapter class implements the ExpectedInterface IncompatibleInterfacespecificRequest() method compatible with the ExpectedInterface

Using the Adapter pattern allows us to reuse existing code that doesn’t match the interface that the client expects, without having to modify that code. Instead, we can write an adapter class that mediates between the incompatible interface and the client’s expected interface.

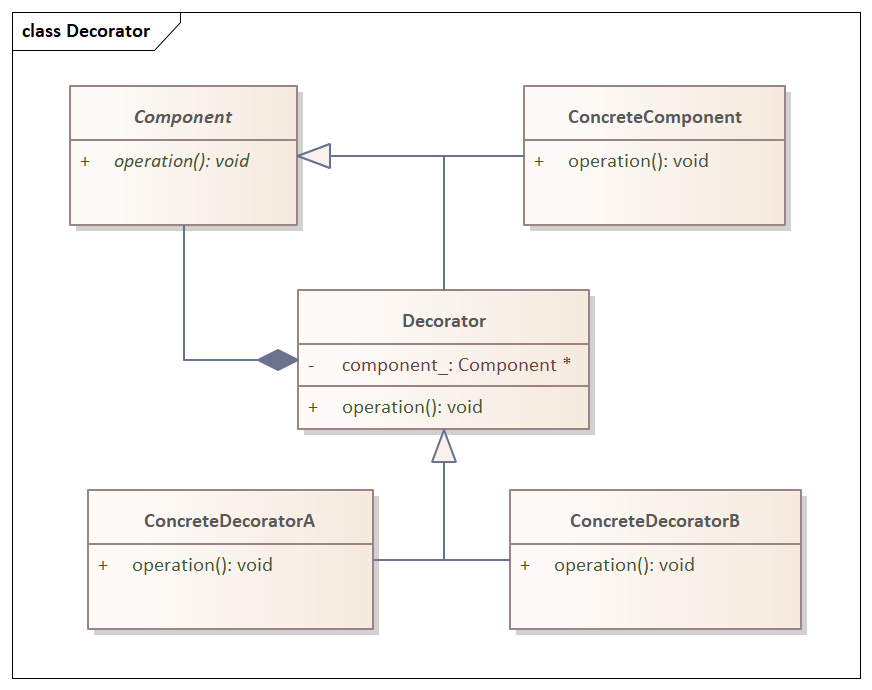

Decorator Structural Pattern

The Decorator design pattern is a structural pattern that allows adding behavior or functionality to an object, without affecting other objects of the same class. This pattern is commonly used to attach additional responsibilities to an object by wrapping it with a decorator object.

C++ Example of the Decorator Structural Pattern

To use this pattern in C++, define an abstract base class that defines the interface for both the component and the decorator classes. Then define a concrete component class that implements the base interface and a decorator class that also implements the same interface and holds a pointer to the component object it is decorating. Here’s an example:

class Component {

public:

virtual ~Component() {}

virtual void operation() = 0;

};

class ConcreteComponent : public Component {

public:

void operation() override {

// Perform some operation

}

};

class Decorator : public Component {

public:

Decorator(Component* component) : component_(component) {}

void operation() override {

component_->operation();

}

private:

Component* component_;

};

class ConcreteDecoratorA : public Decorator {

public:

ConcreteDecoratorA(Component* component) : Decorator(component) {}

void operation() override {

Decorator::operation();

// Add some additional operation

}

};

class ConcreteDecoratorB : public Decorator {

public:

ConcreteDecoratorB(Component* component) : Decorator(component) {}

void operation() override {

// Do not call base class operation() to remove that functionality from this instance

// Add some different additional operation

}

};

Code language: C++ (cpp)In this example, the Component class defines the interface that the concrete component and decorator classes will implement. The ConcreteComponent class is a concrete implementation of the Component interface. The Decorator class is an abstract class that also implements the Component interface and holds a pointer to a component object it is decorating. The ConcreteDecoratorA and ConcreteDecoratorB classes are concrete decorators that add additional behavior to the ConcreteComponent object by calling the Decorator base class’s operation() method and adding their own additional behavior.

Note that if you only needed a single decorator (i.e., you did not require decorators A and B), you can get away with simply adding the necessary additional operations directly to the Decorator class in the example. However, following the pattern as shown requires not much more work immediately and will make it easier when you need to define additional concrete decorators down the road.

Using the Decorator pattern allows us to add or remove behavior from an object without affecting other objects of the same class. It also allows us to use composition instead of inheritance to extend the functionality of an object.

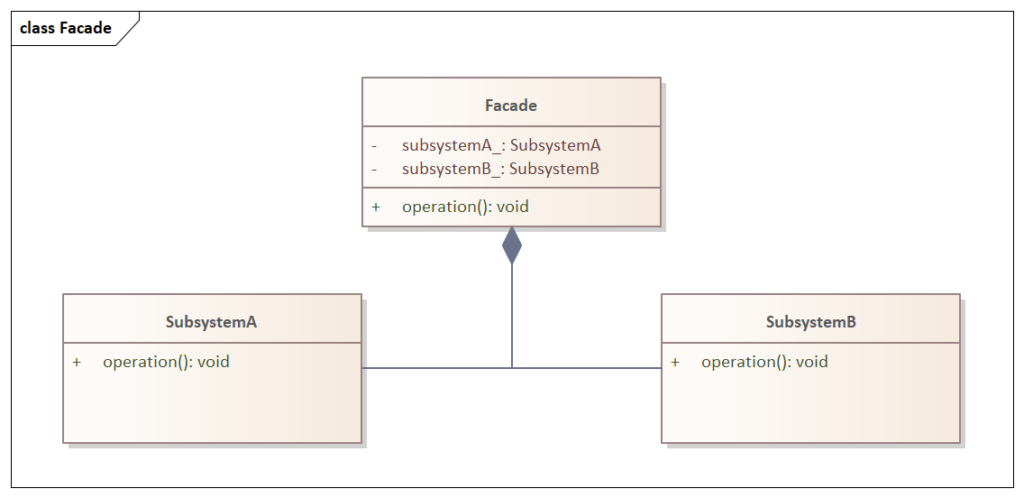

Facade Structural Pattern

The Facade design pattern is a structural pattern that provides a simplified interface to a complex subsystem of classes, making it easier to use and understand. A Facade class can then be used by clients to access the subsystem without having to know about the complexity of the lower-level classes.

C++ Example of the Facade Structural Pattern

In C++, this pattern can be used to create a high-level interface that hides the complexity of the lower-level subsystem. To implement this pattern in C++, we can define a Facade class that provides a simplified interface to the subsystem classes. Here’s an example:

class SubsystemA {

public:

void operationA() {

// Perform some operation

}

};

class SubsystemB {

public:

void operationB() {

// Perform some operation

}

};

class Facade {

public:

Facade() : subsystemA_(), subsystemB_() {}

void operation() {

subsystemA_.operationA();

subsystemB_.operationB();

}

private:

SubsystemA subsystemA_;

SubsystemB subsystemB_;

};

Code language: C++ (cpp)In this example, the SubsystemA and SubsystemB classes represent the complex subsystem that the Facade class will simplify. The Facade class provides a simplified interface to the subsystem by hiding the complexity of the lower-level classes. The Facade class also holds instances of the subsystem classes and calls their methods to perform the operation.

This pattern allows us to simplify the interface to a complex subsystem, making it easier to use and understand. But, my favorite use of it is to isolate clients from changes to the subsystems by abstraction.

Behavioral Design Patterns

Behavioral design patterns are used in software development to address problems related to object communication and behavior. These patterns provide solutions for managing the interactions between objects and for coordinating their behavior.

Behavioral design patterns provide a variety of techniques for object communication, such as using message passing, delegation, or collaboration to manage the interactions between objects. They also provide ways to manage the behavior of objects by defining how they respond to events or changes in the system.

Some examples of behavioral design patterns include the Observer pattern, which allows objects to be notified when a change occurs in another object, and the Command pattern, which encapsulates a request as an object, allowing it to be parameterized and queued.

Overall, behavioral design patterns help to improve the flexibility, modularity, and extensibility of software systems by providing a more structured and standardized way to manage object communication and behavior. They are particularly useful in systems that involve complex interactions between objects, such as user interfaces, network protocols, or event-driven systems.

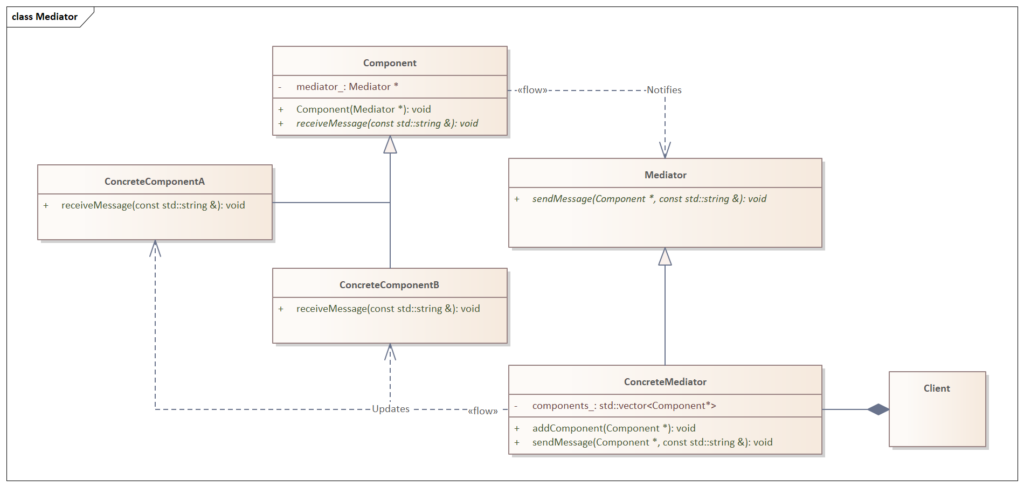

Mediator Behavioral Pattern

The Mediator design pattern is a behavioral pattern that promotes loose coupling between objects by encapsulating their communication through a mediator object. In C++, this pattern can be used to reduce dependencies between objects that communicate with each other.

C++ Example of the Mediator Behavioral Pattern

To implement the Mediator pattern in C++, we can define a Mediator class that knows about all the objects that need to communicate with each other. The Mediator class then provides a centralized interface for these objects to communicate through. Here’s an example:

class Component;

class Mediator {

public:

virtual void sendMessage(Component* sender, const std::string& message) = 0;

};

class Component{

public:

Component(Mediator* mediator) : mediator_(mediator) {}

virtual void receiveMessage(const std::string& message) = 0;

protected:

Mediator* mediator_;

};

class ConcreteComponentA : public Component{

public:

ConcreteComponentA(Mediator* mediator) : Component(mediator) {}

void send(const std::string& message) {

mediator_->sendMessage(this, message);

}

void receiveMessage(const std::string& message) override {

// Process the message

}

};

class ConcreteComponentB : public Component{

public:

ConcreteComponentB(Mediator* mediator) : Component(mediator) {}

void send(const std::string& message) {

mediator_->sendMessage(this, message);

}

void receiveMessage(const std::string& message) override {

// Process the message

}

};

class ConcreteMediator : public Mediator {

public:

void addComponent(Component* component) {

components_.push_back(component);

}

void sendMessage(Component* sender, const std::string& message) override {

for (auto component: components_) {

if (component != sender) {

component->receiveMessage(message);

}

}

}

private:

std::vector<Component *> components_;

};

Code language: C++ (cpp)In this example, the Component classes represent objects that need to communicate with each other. The Mediator class provides a centralized interface for the ComponentConcreteMediator class knows about all the ComponentsendMessage() method to send messages between them.

I like to use this pattern in a system where I have multiple components, such as interfaces to external hardware modules or subsystems. Those interface classes will inherit the ComponentMediator. In this manner, if one ComponentComponentComponentMediator.

Using the Mediator pattern allows us to reduce dependencies between objects that communicate with each other, making our code more maintainable and easier to understand. It also promotes loose coupling between objects, which makes it easier to change the way objects communicate without affecting other parts of the system.

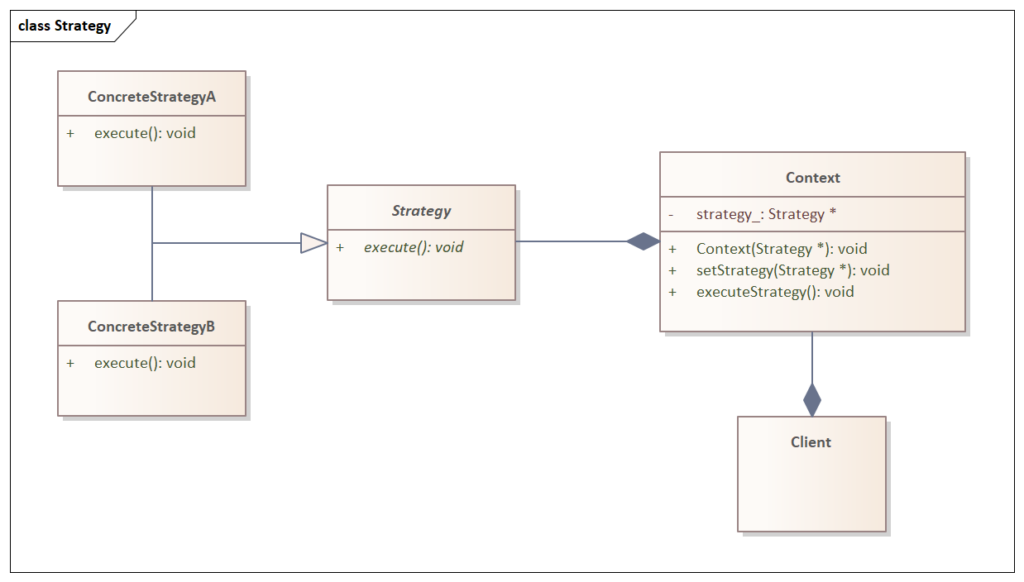

Strategy Behavioral Pattern

The Strategy design pattern is a behavioral pattern that defines a family of algorithms, encapsulates each algorithm, and makes them interchangeable at runtime. This pattern allows the algorithms to vary independently from clients that use them.

I have found this pattern extremely useful when I have an application that needs to support many protocols to various clients. Using the strategy pattern, I can easily swap which protocol is in use at any given time based on the client connection.

C++ Example of the Strategy Behavioral Pattern

To implement this pattern, we define an abstract Strategy class that represents the interface for all algorithms. Then, we can define concrete implementations of the Strategy class for each algorithm. In my protocol case, the Strategy class was my base Protocol class. Then I had concrete protocol classes derived from the base Protocol.

Here’s an example:

class Strategy {

public:

virtual void execute() = 0;

};

class ConcreteStrategyA : public Strategy {

public:

void execute() override {

// Algorithm A implementation

}

};

class ConcreteStrategyB : public Strategy {

public:

void execute() override {

// Algorithm B implementation

}

};

class Context {

public:

Context(Strategy* strategy) : strategy_(strategy) {}

void setStrategy(Strategy* strategy) {

strategy_ = strategy;

}

void executeStrategy() {

strategy_->execute();

}

private:

Strategy* strategy_;

};

Code language: C++ (cpp)In this example, the Strategy class represents the interface for all algorithms. The ConcreteStrategyA and ConcreteStrategyB classes represent concrete implementations of the Strategy class for two different algorithms.

The Context class represents the client that uses the algorithms. It has a setStrategy() method to set the current algorithm and an executeStrategy() method to execute the current algorithm.

Using the Strategy pattern allows us to change the behavior of a system at runtime by simply changing the current algorithm in the Context object. Conscious use of this pattern promotes code reuse, flexibility, and maintainability.

State Behavioral Pattern

I saved my favorite for last!

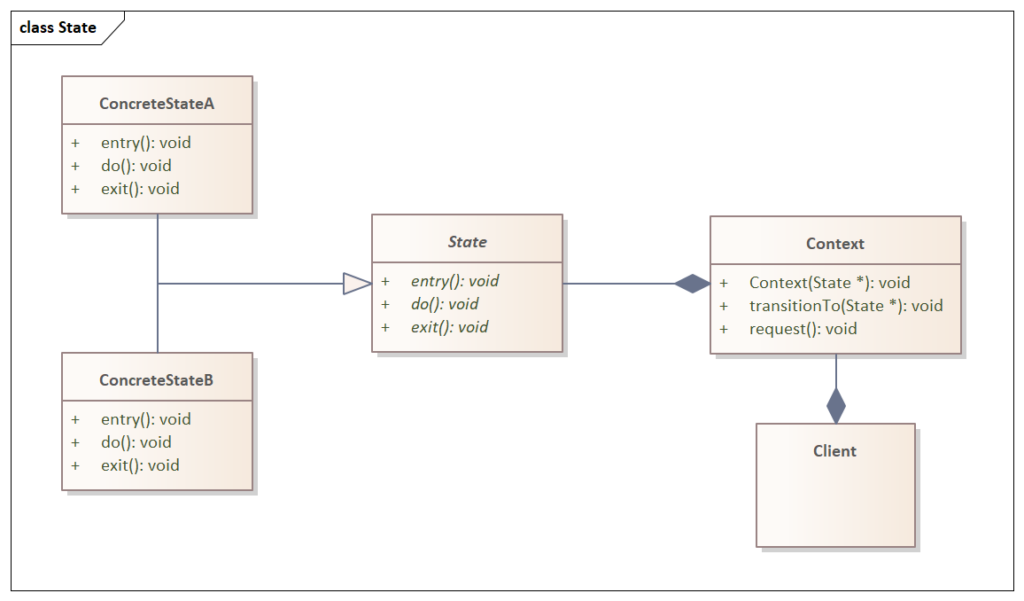

The State design pattern is a behavioral pattern that allows an object to alter its behavior when its internal state changes. This pattern is useful when an object’s behavior depends on its state, and that behavior must change dynamically at runtime depending on the state.

Essentially this boils down to defining a State base class that defines the basic structure for state information and defines the common interface, such as entry(), do(), and exit() methods.

C++ Example of the State Behavioral Pattern

In C++, we can implement the State pattern using inheritance and polymorphism. We create a State base class that represents the interface for all states. Then, we create concrete implementations of the State class for each possible state of the object. Finally, we define a Context class that acts as the context in which the state machine operates. Clients utilize the interface in the Context class to manipulate the state machine.

Here’s an example:

class State {

public:

virtual void entry() = 0;

virtual void do() = 0;

virtual void exit() = 0;

};

class ConcreteStateA : public State {

public:

void entry() override {

// Entry behavior for state A

}

void do() override {

// State behavior for state A

}

void exit() override {

// Exit behavior for state A

}

};

class ConcreteStateB : public State {

public:

void entry() override {

// Entry behavior for state B

}

void do() override {

// State behavior for state B

}

void exit() override {

// Exit behavior for state B

}

};

class Context {

public:

Context(State* state) : state_(state) {}

void transitionTo(State* state) {

state_->exit();

state_ = state;

state_->entry();

}

void request() {

state_->do();

}

private:

State* state_;

};

Code language: C++ (cpp)In this example, the State class represents the interface for all states. The ConcreteStateA and ConcreteStateB classes represent concrete implementations of the State class for two different states.

The Context class represents the object whose behavior depends on its internal state. It has a transitionTo() method to set the current state and a request() method to trigger a behavior that depends on the current state.

You can also make use of templates in the Context class to define an addState() function. In this manner, you can enforce transitions to only a specific set of State classes and utilize custom lambda functions for the entry(), do(), and exit() functions for each state.

Using the State pattern allows us to change the behavior of an object at runtime by simply changing its internal state. This makes our code more flexible and easier to maintain. It also promotes code reuse, as we can easily add new states by implementing new State classes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, design patterns are a powerful tool in software development that can help us solve common problems and improve our code’s flexibility, maintainability, and scalability. In this post, we have explored several design patterns in C++, including the Singleton, Abstract Factory, Adapter, Decorator, Facade, Mediator, Strategy, and State patterns.

While each pattern has its unique characteristics and use cases, they all share the same goal: to provide a well-structured, reusable, and extensible solution to common software development problems. By understanding and using these patterns, we can write more efficient, robust, and maintainable code that can be easily adapted to changing requirements.

As a conscious software developer, it’s essential to keep learning and improving our skills by exploring new ideas and concepts. Design patterns are an excellent place to start, as they can provide us with a deeper understanding of software architecture and design principles. By mastering design patterns, we can become more efficient and effective developers who can deliver high-quality, scalable, and maintainable software solutions.

Additional Resources

Here are a few additional resources for diving deeper into design patterns for software development.

- “Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software” by Erich Gamma, Richard Helm, Ralph Johnson, and John Vlissides. This book is considered the definitive guide to design patterns and is a must-read for anyone interested in the subject.

- “Head First Design Patterns” by Eric Freeman, Elisabeth Robson, Bert Bates, and Kathy Sierra. This book offers a more accessible and engaging approach to learning design patterns and is ideal for beginners.

- Design Patterns in Modern C++ – This Udemy course covers the basics of design patterns and shows how to apply them using modern C++ programming techniques.

- C++ Design Patterns – This GitHub repository contains a collection of code examples for various design patterns in C++.

- Refactoring Guru – This website provides an extensive catalog of design patterns with code examples in multiple programming languages, including C++.

- Software Engineering Design Patterns – This Coursera course covers the principles and applications of design patterns in software engineering, including C++ examples.